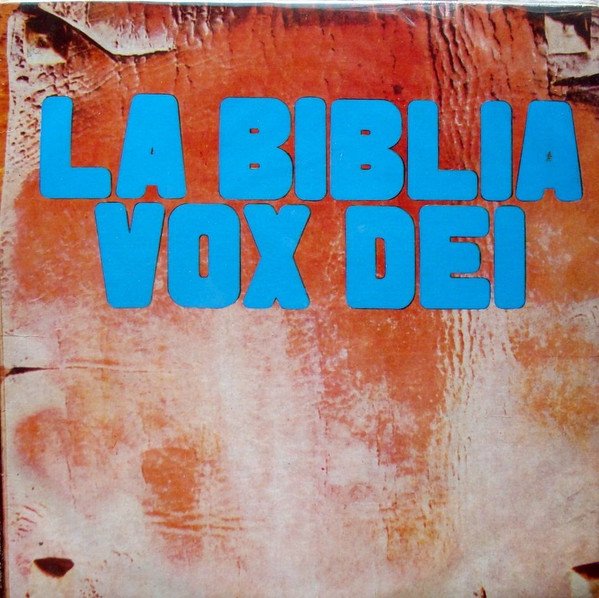

Vox Dei, ‘La Biblia’ (1971)

By King Kenney

Released in 1971, La Biblia begins with an act of refusal. Vox Dei declined the smaller ambitions available to them at the time: the single, the scene, the incremental claim to legitimacy. Instead, they chose totality in biblical proportions. From Genesis to Apocalypse. Beginning and end. Creation, law, exile, war, prophecy, collapse. The decision itself is the album’s first sound.

At a moment when Argentine rock was still negotiating its language and audience, La Biblia treated the album not as a container but as a structure. Each track functions less as a destination than as a passage, moving the listener through narrative and consequence, sometimes sequentially, sometimes in overlapping motion. The music draws from blues, folk, hard rock, and psychedelia, yet these elements never announce themselves for effect. They are absorbed into the work, directed toward momentum and cohesion.

In this sense, La Biblia belongs to an early and relatively narrow lineage. It follows the formal groundwork laid by S. F. Sorrow, which first suggested that a rock album could sustain narrative continuity, and it arrives just ahead of the more theatrically codified successes of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars and Bat Out of Hell. Those later works would benefit from an established infrastructure and a public already prepared for spectacle, conditions that allowed ambition to translate directly into scale and sales.

La Biblia operated under different terms. Its impact was not immediate, nor was it driven by commercial momentum. It moved forward without the assurance of mass reception, proceeding as if rock’s elasticity were already settled fact rather than a proposition requiring validation. As a whole, the record demonstrates how far the form can stretch while remaining intact, even when recognition arrives slowly, through accumulation rather than announcement.

What follows is neither devotional music nor ironic distance. Vox Dei approach scripture as text, myth, and human vestiges, fragments shaped by belief and memory, worn through use. “Génesis” opens without apotheosis, propelled by momentum, as if creation were still unfolding. The music advances with urgency, attentive to process and emergence. “Las guerras” develops with a violence that feels earned, its tension accumulating through restraint. Throughout the album, the sacred is neither untouchable nor disposable. It becomes material, something to be wrestled with, interpreted, and lived alongside.

The album’s significance sharpens when placed against the expectations surrounding Argentine rock at the time. Rock nacional was still defining its contours, navigating between local expression and inherited forms, intimacy and amplification. Vox Dei refused that narrowing. They wrote in Spanish without retreat, drew from Anglo-American rock without deference, and treated spiritual narrative as a serious field of inquiry. The ambition here was not escapist. It was architectural, concerned with how meaning could be built and sustained.

That architecture holds through discipline. La Biblia resists excess even as it embraces scope. Movements arrive and depart with intention. Themes surface, recede, and return altered. The band trusts sequence and duration, allowing significance to accumulate gradually. This restraint is what allows the album’s ambition to remain clear.

Listening now, more than five decades on, the record does not feel fixed in time. It feels patient. Its confidence lies in commitment to form and in a quiet belief that attention will be met with reward. Long before the album as statement became a familiar critical shorthand, La Biblia demonstrated how sound could sustain argument, how ideas might unfold without resolution and remain resonant.

What La Biblia ultimately offers is not an answer to its source material, but a way of engaging with it. Belief and doubt coexist here. History and myth overlap without reconciliation. The album suggests that rock music, when approached with seriousness, can accommodate contradiction without flattening it, and that an album can operate as an ethical space as much as an aesthetic one.

I return to La Biblia not because it announces its importance, but because it never needs to. Its ambition is quiet, its execution exacting, its legacy cumulative. It reminds me that rock’s most enduring gestures often emerge through patience and structure, trusting the listener to remain present without instruction.

Decades on, the record still unfolds. I am still listening.